During the War

Warrior in Action

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. This is not a way of life at all in any true sense. Under the clouds of war, it is humanity hanging on a cross of iron.

— Dwight Eisenhower April 16, 1953

I didn’t know when I flew off the deck of the USS Midway in my A-4C Skyhawk on the night of April 20th 1965 that I was embarking on the worst time and the greatest challenge of my life. I would later describe those endless days and nights of captivity this way: I wouldn’t trade anything in the world for the experiences that I had, but I wouldn’t do it over again for anything in the world either.

My mission was to fly from the Tonkin Gulf where our carrier was on station to “Highway One,” the major transportation route that the North Vietnamese used to carry military supplies to their troops in the south. They did most of their transporting at night when they would be less visible, so that’s when we were sent out to intercept and destroy them.

My wingman and I spotted trucks on the highway and rolled in on our bombing run from 12,000 feet. We descended in a 45 degree dive at full power to an airspeed of over 600 miles per hour and 2,500 feet above the ground. I had the trucks in my sights and pressed the bomb release button on my control stick. Then, instantaneously, my airplane just exploded. All six of my own 250 pound bombs had malfunctioned and exploded under me. The wings and tail section of my airplane were instantly blown away and I found myself hurtling toward the ground in just a cockpit.

There wasn’t a second to lose. I didn’t have even a second to think but my training took over. I reached between my legs and pulled the auxiliary ejection handle. Because I was being thrown against the top of the cockpit by the force of the spinning aircraft – or rather, what was left of it – when the ejection seat slammed into me I was probably six inches above it. It struck me hard as it blew out of the cockpit. But that was the least of my worries. I was already close to the ground and my parachute barely had time – maybe three or four seconds – to open. I remember the silence then, the cold, black night as I descended. But I don’t think my parachute was completely intact, having been partially shredded from the enormous wind blast. Thankfully I wound up crashing down through a canopy of trees. Welcome to North Vietnam.

I would spend the next four days and nights trying to evade the enemy and get out of Vietnam into Laos where I might have a chance of getting a helicopter rescue. But that was not to happen. I was captured by the North Vietnamese, and then spent the next 2855 days and nights as their prisoner.

It was an extraordinary span of my life, with moments of hope and heroism amidst days and weeks and months of pain and despair. There were times when I thought I was about to die; times when I thought that death would be better than what life meant to me then. I learned a great deal in those nearly eight years – about myself, about my country, and my world. I learned the truth about torture up close and personal; since my captors obviously thought of me as a criminal.

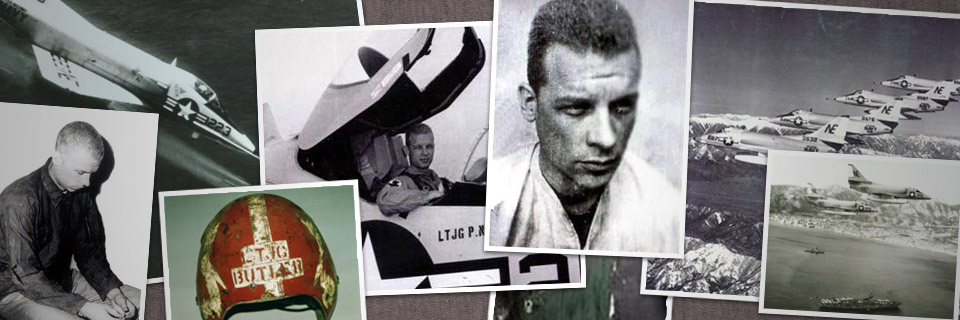

So this “During the War” chapter of my life was not just a horror story, though that was certainly a part of it. More, it was a story of patriotism and honor. For the details, you’ll have to read the book. But I have a page online here with some photographs of that time, and a picture, as the old Chinese expression has it, is worth ten thousand words.